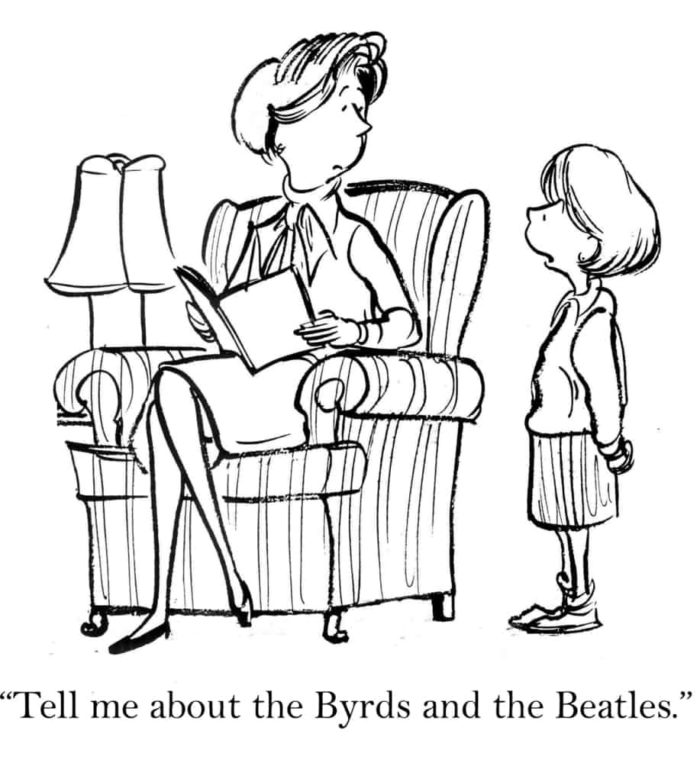

Holding-off Talking to Your Child About Sex? Talk Sooner, Not Later.

I glanced in my rearview mirror, and I could see that one of my friends was clearly distressed.

“I haven’t talked about it with him yet,” she said, and paused. “I think my husband should do it.”

Other friends in the SUV – all mothers of 9- and 10-year old boys – chimed in. They didn’t know how to talk about sex with their kids and they were concerned about it. Some didn’t know how to word it. Some were embarrassed. Some were, perhaps, just procrastinating.

When I was about my son’s age, my mother enlisted my father to read the illustrated book Where Did I Come From? to me and my little sister. We giggled, my mother giggled, and my father probably turned a lovely shade of crimson. The book lays out proper names for body parts and the process of fertilization with 1970s-era cartoon characters engaging in the beginnings of sex. To be clear, they never used the word “sex” in the book, nor intercourse. This was designed to be what they thought was a kid-friendly, family-friendly way to explain the birds and the bees and the closest thing they showed to the deed is of a cartoon Reubenesque man and woman in a sans-clothing embrace in bed. (The book looks to have been updated and I don’t know if my analysis of the book’s current version stands.)

I discovered later that my parents were not typical, in that many of my friends never had a talk about sex education with their parents, or it consisted of everything from “nice girls don’t have sex until they get married” to a throwaway “Dear God please use a condom if you’re having sex”.

“One of the issues for most parents in this country is we tend to think – or project from our own anxieties – that we shouldn’t approach sex education with young children. We’re stuck there,” says Debbie Roffman, a consultant for educators and sex education teacher at a school in Baltimore. “When they are little, these questions are not about sex. They are scientific questions about normal cognitive development. Adults get caught up in their own emotional connections to sex and that frightens them and they back off.”

Exactly, you might be thinking. I can’t talk to my young child about adult sex. But that’s not what it’s about, Roffman says.

“We have a cultural heritage that has led us to believe that talking about sex and related topics could be potentially harmful, but the data shows the opposite of that,” says Roffman. “Children who are raised in a family in which this is part of normal discussion delay sexual engagement for longer than kids who didn’t have this support.”

The nonprofit organization AMAZE, which champions honest, age-appropriate sex education, creates short videos like “How Do You Talk to Young Kids about Sex?” The video backs Roffman’s statement up with a chart that shows that better-educated kids on these topics make better decisions.

I’m seeing this already, both with my son and with other families who have already covered what might be uncomfortable subjects for some parents. Imagine, for instance, the shock and fear a girl would experience with no preparation for what happens to her body when menstruation begins. Knowing what is going to happen and what to do mitigates fear and also prevents kids from assuming that incorrect information is the truth. Further, repeating that message more than once in various ways is what it takes for children to learn it and understand it.

What happens with many parents, Roffman says, is that they freeze up when their children start asking questions related to sex. What escapes the parents is that at developmental ages, kids aren’t asking about sex the way adults understand it, complete with their own experiences and emotional connections. They want to know how things work. They’re asking how something gets from point A to point B: What is the cause and effect that results in a baby?

If you break it down into segments that kids understand, what they’re asking are questions about transportation, causation, and geography. Kids start learning about the concept of time in preschool and they realize, “Hey, I wasn’t always here. There are photos of my family without me in it – why is that?” They’re naturally curious. The answer, Roffman says, is the truth: babies come from a uterus. It’s the same thing as asking, “Where is the car?” and the answer is “It’s in the garage.” Straightforward. Logical.

The key, experts say, is to build a “scaffolding of knowledge” upon which your kids can build comfort. For you and for them, in fact. Conversations can start with the labeling of body parts, which is something many parents shy away from due to embarrassment or lack of experience in talking about it.

For many parents, however, it may feel like a leap the size of the Grand Canyon to talk about the act of sex. It’s science, or mechanics, at its basest explanation: this part must be inserted into this part, and a biological reaction is a result.

Even Roffman, now a certified sex educator, needed practice.

“I didn’t grow up this way,” she says. “I was a sexual illiterate; I didn’t know much about it or how to think about it. What I learned when I fell into this job by accident is that practicing saying these words in the mirror and separating them from my discomfort, I found they were just words. Practice saying these words in front of an infant out loud so they become natural before they understand what you’re saying.”

If we’re afraid that our children will bust out the word “penis” in public, whose needs are we really focused on? Ours, or theirs?

Now that my son is 10, we have had conversations about love, and sex, body parts, and erections. Sometimes I still trip over the words, but I coax them out for the sake of his education, and he, so far, does not flinch. He knows he can ask me questions, like the time we were watching a movie and the female character was unmarried and pregnant. Or one night before bed he stuck his tongue out and started wiggling it and asked me that’s what a French kiss looked like.

I can’t police all of the information that reaches his ears at school, during basketball practice, or with friends. But what I can do is model is that I’m his go-to source for anything he wants or needs to know. And if I’m doing my job right, not only will he be well-informed, he’ll have enough situational knowledge to make good decisions as he grows up.

I found some basic tips on the AMAZE site to help parents who may be nervous or unsure of how to begin:

1. It is never too early to start having conversations, and it’s on you to start them. Remember, brief, more frequent talks are more effective than one big talk.

2. Kids just want the basics. Find out what they know and go from there. You can’t share too much. What they don’t understand goes over their heads.

3. You don’t need to know all the answers. Be honest and tell them you don’t know but you can research it and get back to them. Then follow-up.

4. There are no gender-based rules when it comes to conversations.

Talk to your young kids about consent early on. It’s about body autonomy, not sex.

“Of my four kids, each wanted to know things at different ages,” says Dr. Gilboa. “As parents, I’d say the same things as I’d say about drugs, alcohol, and so on: you want to be your child’s first best expert. You want to be their go-to person – if you defer being your kids’ go-to person, they’ll ask someone else. They’ll think, ‘Oh, I guess I can’t ask my parents about that.’”

Don’t leave your kids’ sex education to chance, says Roffman.

“It’s just like math – you can’t teach your kids all the math in the world at one time. Instead, think of it as building blocks,” she says. “Tell them, ‘Let’s start here and then I want you to think about it and we can talk more about it.’”

The same math lesson isn’t taught to a kindergartener at five as it is to a 14-year-old teenager; you’ll teach it differently.

The most important thing, Roffman told me, is to be truthful. Lying or making up fairy tales will hurt your credibility, in the long run. That’s not to say that you have to be 100% transparent from day one, she says. You know your kids. You’ll be able to tell what they’re ready to hear. Keep the door open for discussion, and when it comes time for your child to ask you the questions that matter, they’ll know that you’re willing to tackle it with them.

More about Sex Education from Alpha Mom:

1. How to Have the Puberty Talk

2. Talking To Young Children About S-E-X

3. How to Talk About Sexual Consent with Your Kids

Photo sources: Depositphotos/emevil (top photo) /andrewgenn (cartoon)